It all made for interesting socializing. The overarching impression, however,

was the sensitivity to the customs, culture, and ways of the others. And

the incredible hospitality of the Saudis.

Everywhere, there are watchtowers where the men would keep lookout for raiding parties from rival tribes.

Today, the towers are crumbling from neglect, but the wells are still used to irrigate crops.

Several hours drive from Al Baha, in the mountains, is an old village built on an outcropping of white rock and

called by its nickname, the Marble Village. I had not heard of it, but when visiting in the city of Al Baha, I

struck up a friendship with a local Saudi. He asked if I had seen it, and when I said I had not, he

offered to take me there, and the next weekent, we went. It appeared deserted when I toured it, but there is a working

banana plantation just below it, well tended and irrigated from a spring that gushes forth out of the rock above and behind

the village. The outflow from this small spring was cleverly channeled down the hillside to and through

the banana palms. Whether or not it may have served as a water supply for the village itself, I do not know. But

it supported a lush growth of trees and other vegetation around the village.

This is one of the most mysterious, lovely, and remarkable places on the planet.

The Marble Village

Also known as Dhee Ayn, it is a 400 year old abandoned stone settlement

built atop a marble hill. It is 24 km south of Al Bahah along Al Aqabah Road.

The village is surrounded by Palm groves, banana, vegetable and herbal plantations,

a permanent stream and natural wilderness.

The "source" of the irrigation water

Some personal notes and thoughts about Yemen

The Asir of Saudi Arabia blended with the adjacent highlands of northern

Yemen. Many of the peoples, families, and clans in that area lived on

both sides of what is today the "official" border between the two nations.

But for centuries, that boundary was fluid at best if not downright

theoretical, as tribal loyalties determined geographic control of the

lands.

As mentioned above, in the history of the Saudi Red Crescent Authority, that

organization began in the 1930s in part to care for soldiers wounded in the

war then on-going between Saudi Arabia and Yemen. There have been many

wars between the two parties in the decades since despite a

"peace treaty" defining a formal border in 2000.

Yemen has a long and complicated history of internal conflicts often

exacerbated by "assistance" to one or more of the warring parties by

outsiders, not unlike the present day War in Yemen.

This complex history can be partially understood by series of

"half-truth" about the country.

The northern part of Yemen is

mountainous and populated by tribes with fierce loyalties and

long history of inter-tribal warfare. Through

most of recent (20th century and beyond) history, the capital of

this northern part of Yemen has been Sana'a, an ancient city at the

foothills of the mountains. It was where the first "king" of

modern Yemen, Imam Yahya, lived and ruled from, who was

recognized as king by Italy in 1904. His reign was marked

by isolationism, supression of dissent, and neglect of

development of infrastructure and education. This king was

succeeded upon his death in 1948 by his son, Imam Ahmad. Ahmad

relocated the capital to Ta'izz and began a program of

economic and social development. But, upon his death in

1962, there was a coup led by the military with the death

or exile of many of the royal family and the capital

was returned to Sana'a. Rural hill tribes opposed the new

government, and with the support of Saudi Arabia (and Britan

and Jordan) launched

the North Yemen Civil War, opposed by the "republicans",

backed by Egypt and the United Arab Republic. The civil

war ended in 1968 with the victory of the republicans and the

declaration of the Yemen Arab Republic, a socialist entity, but

conflict among various parties continued for years afterward.

In the meantime, there was a British "Protectorate" in the

southern part of the country. The British had seized the

port of Aden in the mid 1800s to serve as a coaling station

for the British East Indian Company ships sailing to and from

the "far east". The British had also made alliances with multiple

adjacent tribal entities, to provide a buffer

zone of thousands of acres protecting the port

and creating the Aden Protectorate. By the late 1950s and early

1960s, the rising tide of Arab Nationalism threatened

the stability of the Protectorate. That, plus the loss of

former British colonies (India) made the usefulness of

the port of Aden marginal at best, and the British withdrew

from Aden in 1967 without arranging follow up governance.

After the British withdrawal, the Yemeni National Liberation

Force took over and proclaimed the Republic of South Yemen, later

the Peoples Democratic Republic of Yemen, a socialist nation.

Relations between the two Yemens varied from quietly hostile to

open warfare, with each side receiving support from outside sources.

In the late 1970s, the Arab League brokered a peace treaty that

included committment to unification of the two states. But civil

wars among various partied continued in both the north and south

and between the two.

In 1990, the two governments agreed on a plan for joint

governing of Yemen, and the countries merged in May 1990.

The leader of north Yemen became President and that of

South Yemen, Vice President. There was a unified

parliament formed and elections held in 1993.

But after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990,

Yemen's president opposed military intervention by any

non-Arab nation, and Yemen, a member of the United

Nations Security Council at the time, voted against the

use of force resolution before that body.

But as mentioned elsewhere, the U. S. and Saudi Arabia

had an agreement by which the U.S. would defend the Kingdom

if it were attacked. At the point where Iraqi forces

seemed poised to move into Saudi Arabia, the U.S. intervened

in the coflict.

Yemen's opposition in the U.N. Security Council to

several resolutions amounted to support for Iraq in

Saudi eyes, and the Kingdom abruptly expelled the

nearly one million Yemeni living and working in Saudi

Arabia as punishment for the Yemeni government position.

Before that time, Yemeni had been free to move easily

to and from Saudi Arabia and they constituted a large and

valuable part of the expatriot workforce in the Kingdom. They

were suddenly (and remain) persona non grata and were forced

out.

Political instability increased in both Yemens, and

in 1994 a civil war between the North and South broke out

with Saudi Arabia supporting the South Yemen forces. The

South lost the civil war and most of its leadership fled

the country.

By 1999 there was a unified government again under

the elected president Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former

president of North Yemen, who governed from Sana'a.

But political unrest continued and by 2000 there were

multiple terrorist attacks, generally by al-Quada

affiliated groups, Sunni Muslim fundamentalists.

In 2004, a Shia group termed the "Houthi" for their

leader Hussein Badreddin Al-Houthi began an uprising

against the Yemeni government alledging discrimination

and government aggression against the Shia.

The Shia insurgency in Yemen began in June 2004 when

dissident cleric Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, head of the

Zaidi Shia sect, launched an uprising against the Yemeni

government. The Yemeni government alleged that the Houthis

were seeking to overthrow it and to implement Shi'a religious

law. The rebels counter that they are "defending their community

against discrimination" and government aggression. Ultimately,

the Houthi drove the government out of Sana'a to Aden

The Yemini military has been conducting a war against the Houthi

forces since that time. Al Queda remains active in Yemen also and

generally opposes the Houthi rebellion but concentrates largely

on U.S. targets. Saudi Arabia joined the conflict in 2014, supporting

the Yemeni government agains the Houthi.

The Yemen war thus evolved into a proxy war between the Sunni

Muslim nation of Saudi Arabia and the Shia Muslim nation of Iran, which

supports the Houthi.

And the Yemeni pay the price.

'

Brief History of the House of Saud

The al-Saud family was originally from

Ad-Diriyyah, a small town to the north of Riyadh, but they fled that town around 1890 when a rival

tribe, the Al Rashidi allied with the Ottoman Turks, raided and destroyed Dariyah and captured

Riyadh.

The Saud family fled to Kuwait where they lived in exile for nearly 20 years.

Abdul Assiz al Rahman Al Saud, (later known as "Ibn Saud") the son of the deposed emir,

returned in 1901 and worked to unite tribes of the desert region to the east and south of Riyadh,

the "Nejd", building alliances and eventually

recapturing the city of Riyadh in a daring nightime raid on January 15, 1902.

After the return of the Saud family, they remained in Riyadh and did not rebuild

their former home. Diriyyah was preserved a ruins and was available to tour as

a reminder of that part of the history of the House of Saud and the treachery of

the Al-Rashidi in allying with the Turks.

After the capture of Riyadh, many additional tribes joined Ibn Saud and over the next several years,

his forces recaptured most of the Nejd from the Rashidis, who then appealed to the Ottoman Empire

for military aid. The Ottomans sent troops into Arabia to assist the Rashidi, but Ibn Saud waged

a successful

guerilla war against the Turks and they withdrew. By 1912, Ibn Saud controlled the land all the way

from Riyadh to

the eastern coast of the peninsula, on the "Arabian Gulf".

Throughout this time, Ibn Saud worked closely with the strict, ultraconservative, Islamic religious order,

the Wahhabi, founded in the 1700s by followers of Mohammed Wahhab of the Nejd. Mohammed Wahhab had earlier formed

an alliance with Mohammed ibn Muqrin Al Saud, the emir of Ad-Diriyyah deposed by the Al Rashidi and father of

Ibin Saud. Diriyyah was an agricultural community and the ancestral home

of the Al Saud tribe.

After the conquest of the Nejd, Ibn Saud founded the Ikhwan, a military-religious brotherhood

which assisted in his conquests combining the zeal of conservative Wahhabi Islam with his

military needs of the day. This union and continuing close relationship of the Saud family and

the conservative fundamentalist Wahhabi was critical to the expansionn and creation of what

became the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and has implications and repercussions stil.

During World War I, the British government established diplomatic relations with the newly

formed "House of Saud" and its new King, Ibn Saud. The British provided financial and military

support to the new "nation" as Ibn Saud contined his war against the Al Rashidi, allies of the

Ottoman Empire.

As an aside, the activities of "Lawrence of Arabia" and his guerilla warfare to distupt

Ottoman Turkish supply lines took place in the western part of the peninsula, also known as

the Hijaz, where Mecca, Medina, and Jeddah are located. These raids were often directed at the

"Hijaz railroad" connecting the port of Aquaba at the top of the Red Sea with Jeddah a port

along the eastern coast of the Red Sea and a major shipping point and access to the

Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina. During this time, the lands

west of Riyadh and the Hijaz were not under control of the House of Saud.

After World War I, Ibn Saud continued his war against the Rashidi, the latter now without

the aid of the Ottomans, defeating them at the Battle of Hai'il in 1922. In 1925, Ibn Saud

completed his conquest of the western provinces by capturing Mecca.

and on 23 September 1932, united his

dominions into the "Kingdom of Saudi Arabia", with himself as its king.

As another aside, the Holy City of Mecca had been under the control of the Hashemite clan ("Hashimi"),

direct descendents of the Prophet Mohammed, for seven centuries.

In 1908, the Hashemite Hussein bin Ali was appointed Sharif of Mecca, an honorific term denoting a ruler who

is a direct descendent of the Prophet. The Hijaz was then under control of the Ottoman Turks, and

Hussein gradually developed ambitions for

an independent Arab Kingdom in the peninsula. During World War I, this interest in Arab nationalism

among Hussein and his sons, Abdullah, Faisal, and Zeid, led to their involvement in the "Arab Revolt"

against the Ottomans in 1916, an uprising that had been discussed and negociated with the British

since at least 1914.

Hussein had big ambitions and wanted to have the entire Arab peninsula,

Greater Syria, and Iraq under his family's rule. He looked for British support for this idea,

but found no support for his grand plan although the British probably did promise to

support a smaller kingdon in the western provinces. The Arab revolt,

an Anglo-Hashemite venture, finally broke out in June 1916. Britain financed the revolt and

supplied arms, provisions, direct artillery support, and experts in desert warfare including the

famous T. E. Lawrence. The Hashemites promised more than they were able to deliver,

and their ambitious plan ultimately collapsed for lack of support among other Arab

nationalists, especially in the areas later Syria and Iraq. But the guerilla war against

the Turks was effective in tying down Ottoman resources, and Hussein's son Faisal was a commander of Arab

forces working in collaboration with Lawrence and the British.

After the war, the British devised a "Sharifian Solution" to partially fufill some of the

conflicting committments they had made to various Arab groups.

This "solution" proposed that Hussein's son Ali would succees him as Sharif of Mecca and

two other sons of Hussein would be

installed as kings of two newly created countries across the Middle East: Iraq and Transjordan.

Abdullah, became the Emir of Transjordan in 1921 and King of Jordan in 1946. His descendants

continue to rule the kingdom known ever since as the "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan". Abdullah was

assassinated in 1951, but his descendants continue to rule Jordan today.

Faisal, briefly proclaimed King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria in 1920, until he was removed by

France, who wished to remain in charge of Syria. Faisal then became King of Iraq in 1921. In Iraq,

the Hashemites ruled for almost four decades, until

Faisal's grandson Faisal II was executed along with the crown prince and other members of the

family in the 1958 British-backed military coup d'état. This was the definitive end of the

Hashemite dynasty in Iraq.

In case you were wondering where the messiness of the "Middle East" came from: blame the Brits.

And the French. They drew up the national boundaries without regard for tribal, ethinic, or

religious loyalties and continued to keep things stirred up to benefit their national and

imperial interests. The U.S. has simply continued this long sad story.

We went to or through England a few times, both to and from Riyadh or on

the way to other places. Here are a few pictures from London area and Brighton

just to show we were there and did all the tourist things. We even saw some

theatre there, on memorable time was taking the kids to see "Starlight

Express", the entire cast on roller skates zooming around the entire

theatre as they enacted the story of Rusty, the obsolete steam engine, who

dreams of glory by winning a great train race against the diesel champion.

The show was by Richard Stilgoe with music by Andrew Lloyd Webber. On a

later trip, I got to see the original London production of "Phantom of the Opera",

another Stilgoe-Webber pairing.

One very nice, relaxing trip was to the Canary Islands. We traveled first to Spain,

spending a little time there, before traveling on Iberia, the national Spanish

airline, to the Islands. Flying on Iberia was very nice and the food was great.

Once on Gran Canaria, we spent most of our time on the beach.

Many years later, after we moved back to New Orleans, we found out about

the "Islanos", an ethnic group of people descended from Canary Islanders, who

were brought to the Spanish Lousisiana territory in the late 1700s. There were

perhaps over 1,000 individuals settled in the lands downriver from New Orleans,

in part as protection from a possible British invasion of the lower Mississippi

River area. Over time the original settlers intermarried with local populations

and eventually lost their Spanish language and culture. Perhaps the most

prominent Islano was Leander Perez, the infamous "judge" who ran Plaquemines Parish

from the 1930s thorough the 1960s, known mostly for his extreme racist views and

the ruthless fashion in which he enforced segregation in Plaquemines and St. Bernard

Parishes. When we lived in New Orleans in the 1960s, Gene worked at the

Public Health Service Hospital, the "Marine Hospital", in New Orleans. The

active duty military personnel who worked there or were patients there could

not even buy gas at service stations in Plaquemines Parish because the U.S. Army

had been integrated in the 1950s. A strange thread of connection among

parts of a life.

The time on the Canary Island beaches was a great change from living

in Riyadh. Most of the tourists on the beaches at that time were from Europe,

mostly Spain and Germany, as the Canaries were a favorite, low cost, vacation

place, easy to get to on Iberia Airlines. The topless sun bathing women were

a notable change from living in Riyadh, also.

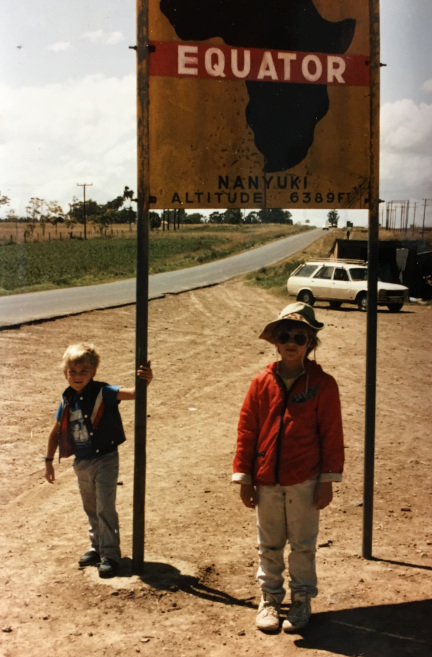

On one of our vacations, we traveled to Kenya and went on a ten day safari. The

trip had been arranged through a local travel agent in Riyadh, who had booked our

excursion with one of the many Kenyan "safari companies" based in Nairobi.

We traveled by air to Nairobi, arriving late at night, and were met by a representative

of the safari company and taken to a lovely hotel for that night. The next day

we met our driver, Barak, and our travel companions. The trips were in a

Nissan mini-bus with a maximum capacity of eight people. We were five, and

were joined by a very nice young British couple who were living and working in

the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. They were, fortunately, also very kind and

patient about traveling with three young children.

The next day, we traveled north to Samburu Lodge, where we stayed a day or two.

The Lodge had a night-time observation station by a waterhole there, and adjacent

land in a game reserve was teeming with animals. Barak threaded us through herds

of elephants and giraffes and sought out other animals for the photographers

in our party. The lodge was also a fine place to stay and relax after the

rather long drive up from Nairobi.

Then we headed south, stopping at the Mount Kenya Safari Club. The "Club" was

a grand hotel, now a Fairmont Hotel, which started its days as a hunting

lodge in the early 1900s. Sometime in the 1950s, William Holden, the American

actor and some friends bought a large parcel of land including the lodge and

founded the Safari Club. Sometimes called "Hollywood in the Wilds", it

became a luxury resort providing game hunting safaris to the wealthy. It was

a lovely, if over the top, place, and the dinner buffets were beyond compare.

Entertainment there included bird-watching, game-watching, and people-watching.

There was even a troupe of local native dancers-drummers on the huge lawn

in the afternoon.

From there, we headed south west to the Masai Mara, staying at Cottar's Camp.

It's the oldest lodge in Kenya's Masai Mara wildlife reserve, with tented bedrooms,

a luxurious main lodge, and a bar and lounge in a covered pavillion without walls,

overlooking the open bush. In the afternoons and evenings, there was a large

fire in a fire pit near the bar above the rows of tents where we sat and watched

huge herds of animals on the plain.

There are animals everywhere, and they freely wander through the camp and among the

tents, especially at night. The staff at the Camp is largely local Masai and

they serve as guides for walking safaris as well as security, especially during

the night. The white guides carry huge caliber rifles or shotguns. The Masai

men carry only their six foot long wooden spear.

The Cottar family was perhaps the only white

family given permission to establish a safari camp within the huge Masai Mara

game preserve, due largely to the patriarch of the family, a prominent American "white

hunter", who was known for his good relationships with the Masai anf for befriending

local tribal communities. His son

founded the camp in the 1920s and was later fatally gored by a rhinocerous. As

he lay on the ground bleeding to death from his mortal wound, his companions

rigged a sun shade for him to make him more comfortable, but he asked them to remove

it, as he wished to die looking at the African sky. If you stay at Cottar's Camp,

you will understand this.

Overall, the experience was a strange mix of left over elements of the days of

Colonial rule in Kenya in the main lodge and the bar, coupled with the

feeling that here, the animals are in charge, and it is only the Masai who

are truly adapted to and comfortable with, that world.

After a few days at Cottar's Camp, Barak asked us if we would be interested

in visiting a Masai village. We, of course, were happy to do so. At the time,

we hardly recognized what a splendid and unusual opportunity this was.

Evidently Barak had found us suitable to arrange such a visit. He had

sought out a nearby Masai women's village and made (or renewed) the acquaintance

of one of the women there. Barak spoke several languages: the language of his

own tribe and village, Swahili, the cobbled together trading language combining

Arabic, several local languages, and a bit of English, and, of course, English.

Our hostess at the village spoke Masai and enough Swahili to communicate with

Barak.

We drove to the village and spent a few hours there. This was a "Woman's Village",

and only women and young children lived there. More on this later.

The houses were made of

saplings plastered with dried cow dung. Since the area is dry most of the year,

except for a brief rainy season, the homes were weather tight. The women

built and maintained the homes. Each had a small cooking stove which also

provided heat. There were perhaps twenty women living there along with many

children. The houses were surrounded by a fence of rolled up and twisted thorn

bushes, with a gate opening at two locations. The fence also kept the

goats, the only livestock there, corraled and safe from predators. At night,

Masai men, who lived in their own village nearby, came to the women's village

and secured it for the night by rolling additional thorn bush barriers into

the gate openings.

The women and children were as curious about us as we about them. Our middle

son, Rob, was heavier than our other two sons, and the Masi were quite interested

in him and kept touching him, as they had never seen a child before who was not

as skinny as they. Barak explained their interest in Rob to us later. Rob, however,

later told us he had thought they wanted to eat him.

The Masai separation of the sexes was interesting to us, paralleling in a way,

the Saudi traditional customs, but more extremely so. What we learned follows.

The Masai believe they are God's chosen people. The evidence for this is that

God has given them cattle. Cattle are therefore sacred, and the duty of the Masai

is to raise the cattle, see they are fed, and protect them. Although Masai do

drink the blood of their cattle for nourishment, they rarely slaughter one

except for special occasions. The adult men are responsible for tending the

cattle, acting as herdsmen, and moving with the cattle to various locations

as the animals graze the plain. The men do not farm the land, for to do so

would break up the soil and kill the grass, which is what the cattle eat. Adult

males are also members of a society into which they are initiated at puberty.

Formerly, one final rite of passage was for the young male (a "junior warrior")

to go into the bush armed only with the short spear and to kill a lion. Although

when we were in Kenya, this practice was said to be abandoned, the Masai men

all still carried such a spear. They were clothed in a red cloak and we often

saw them against the sky in the cloak, with the spear across their shoulders.

Once, when we were driving in the area, we saw several lions who were hunting.

A short distance away, we saw two Masai men along the roadway and Barak stopped

to tell them there were hunting lions nearby. After several minutes of conversation,

we were again on our way down the road. When asked about what the Masai had

said when informed there were lions about, Barak quoted them as saying "We do

not fear lions."

Masai women lived in separate villages as described above. These villages were

relatively permanent in location and the women did some food gathering in the area

and some gardening, within the village confines. The women bore their children

in the village, and, after that, the woman remained in the village with the child,

nursing, for at least two or more years, not seeing her husband during that time.

Aferward, the woman would begin to see her husband again, spending time with him

at the men's village until pregnant again, when she returned to the women's village.

Children were raised in the women's village until near the age of puberty. At that time,

the boys became "junior warriors" and would leave the village to spend time with the

adult men, the "warriors". The girls remained in the women's village until they

developed menstruation, at which time they were initiated as adult women and married

a junior warrior.

Both boys and girls passed through several stages of maturing into adults, the boys

with the adult men, and the girls with the women. These stages included learning about

the duties of an adult and also multiple rituals and trials, including circumcision for both

males and females. Individuals passed through each stage of maturation with a peer

group of other of the same gender and approximately the same age.

At the time the boys left the women's village to live as junior warriors and begin

the path to adulthood, the girls of similar age became sexually active. The young

girls and young warriors would meet together outside the women's village and

during this period, usually would select a life partner for later marriage. But once the

girls experienced menarche and pregnancy was possible, their initiation into adulthood was

completed and they were married to the partner of their choice. The new couple would then

live together in the man's world until the wife became pregnant. At that time, she would

return to live in the women's village and the cycle would repeat.

In a land with scarce resources incapable of supporting large human populations, the

Masai way of life seemed to combine prudent population management with careful management

of resources needed to sustain life.

Some picures at the Mount Kenya Safari Club - the fireplace in the main lodge during the

cocktail hour, and the dancers drumming on the lawn below the lodge.

Samburu lodge and the game preserve adjacent. Many of the pictures of the

animals were taken with a 200 mm lens, so we were not a close at it would appear.

At least not dangerously close. The only animal Barak feared was the rhinocerous,

an animal Barak regarded as ill-tempered, stupid, and unpredictable.

The first pictures are from Samburu. Then there are pictures taken on

our travels down to the Masai Mara, then pictures from the Mara and finally,

pictures from our visit to the Masai village.

Barak was a wonderful guide with great knowledge of the animals and the country.

At one point, we came across two young male lions who were being persued by

two or more young male buffaloes. Barak explained that the buffalo and the

lions were enemies and that the buffalo protected their young from lions by

herding together with the young in the center. The herds consisted of females and

the young and a dominant male. Young males, who might be a threat to the dominant

male were excluded from the herd and lived on the outskirts of it. These young

male buffalos also protected the herd from lions. In the case of the pursuit we

observed over an hour or more, the buffalo were chasing down two young male

lions. The lions were males similarly excluded by a dominant male from the pride

they had originated in. They were out hunting on their own and also looking for

a mate. The buffalo had chased them away from the buffalo herd and as we watched,

the buffalo chased the lions over perhaps a mile or more. The lions, which

do not travel large distances rapidly but are specialized to make short

runs at bursts of high speed, were visibly tiring from the continuous chasing

of the buffalo, which could trot briskly over long distances without fatigue.

Barak explained that the outcome of this chase would be the death of the lions.

So much for the "king of the beasts". We did not stay around for the end, however.

There are nine species of giraffe, each with differing markings. In Kenya the three species

found are:

The Masai Giraffe (most common, perhaps 15,000 individuals) located in Amboseli, Masai Mara, with

dark, irregular, jagged, star shaped blotches that extend to the hooves.

The Reticulated Giraffe

(aka Somali Giraffe) perhaps 8,000 individuals) located in northern Kenya (Samburu) with

clearly defined polygonal liver-colored spots, often dark, separated by bright white lines and a

pattern that may extend to the legs.

The Rothschild Giraffe (aka Ugandan Giraffe) perhaps 1,000 individuals) in protected areas of Kenya.

Markings similar to Masai Giraffe but less irregular and of lighter color, separated by a more cream

colored border. Legs are white.

On our trip, we saw the Somali Giraffe in Samburu and the Masai Giraffe in the Masai Mara.

The photo on the right, below, shows the two male lions being chased by young buffaloes as

described above.

There are three species of Zebra, two of which are found in Kenya:

The Plain’s Zebra (aka Burchell’s or Common Zebra) weighs about 450 – 550 pounds,

has a heavier body and shorter legs than the Grevy’s zebra and is found in the

south and east of Kenya (Masai Mara). It has wider stripes which cover the belly

and tend to be more curvy than those of the Grevy’s Zebra.

The Grevy’s Zebra is an endangered species found in northern Kenya (Samburu).

About 2,000 individuals remain of the 15,000 present in the 1970s.

It is larger (750-950 pounds) and taller than the Plain’s Zebra and has thinner

stripes which are straight, larger ears, and a white belly. The stripes do not extend across

the belly.

The third Zebra Species, the Mountain Zebra, is found in south and south-western Africa.

It is intermediate in size between the other two species and has a white belly like the Grevy’s Zebra.

One of the more remarkable parts of our trip to Kenya was the

opportunity to visit a Masai women's village. Here are some pictures of the visit.

There is more information on the Masai and our visit above.

Other tourist photos from Kenya trip.

The US-Saudi Arabian Joint Economic Commission (JECOR)

JECOR is mentioned in the excellent book "Confessions of an Economic Hit Man" by John Perkins (2004),

which provides a truthful, if unfavorable, look at the organization, and some of the

shady aspects of its early days.

The origin stories that circulated among the "old hands" at JECOR during our tenure are helpful

in understanding how things really operated and the purpose of it all. In this version

of reality, the Joint Economic Commission was created during the "oil crisis"

of the late 1970s, when the price of oil skyrocketed and a massive flow of money

gushed into the little Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and other oil-producing nations. The

transfer of wealth during that era rivals that of the flow of wealth (gold and silver) to Spain during

the conquest of the Americas. In the case of Spain, that nation embarked on an ill-fated

militarization and wars of conquest, with disastrous results, long and short term. In the

case of Saudi Arabia, the nation did not embark on military mis-adventures but rather

began an ambitious program of infrastructure building, reform of agriculture and

diversification of the economy, and huge social support programs.

In the case of Saudi Arabia, the reasons for it's not spending on a military build-up

extend back to the time between WW1 and WW2, when the new country of Saudi Arabia, a

"Kingdom", was largely ignored by the European powers, but was treated with respect

by the United States, particularly under Franklin Roosevelt's administration. During that

time, the Americans obtained a virtual exclusive lock on Saudi oil through the

joint venture "ARAMCO". Today's Saudi Aramco, also called Saudi Arabian Oil Company,

was formerly the Arabian American Oil Company, the oil company founded by the Standard Oil Company

of California (Chevron) in 1933, when the government of Saudi Arabia granted it a concession.

Other U.S. companies joined after oil was found near Dhahran in 1938.

In addition, later negociations between the two nations resulted in an agreement that

the US would protect Saudi Arabia if the later nation ever needed defending in a

military way. This agreement was in exchange for Saudi Arabia consenting not to build up its military. This

agreement was widely viewed as a protection for the new state of Israel.

Sometime during this massive transfer of wealth from the US to Saudi Arabia,

shortly after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, American leadership,

in the person of Henry Kissinger, moved to develop improved relations with the Arab

nations. Since by that time, the price of oil had increased from about $1.39 per barrel to

$8.32 a barrel, there was also a need to find means to return these "petrodollars"

to the US, which was bleeding cash to the oil producing nations. The actual scheme

was developed and implemented by William Simon, the Treasury

Secretary during the Nixon and Ford administrations. That scheme was the Joint Economic Commission.

The Commission’s objectives at the time it was created:

“Its purposes will be to promote programs of industrialization, trade,

manpower training, agriculture, and science and technology.”

The participating Saudi government agencies were the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance and National Economy,

the Ministry of Commerce, and Industry, and the Ministry of Planning. On the US side,

the managing agency was Simon’s Treasury Department. This was an unusual arrangement,

because such international government to government assistance programs would fall

under the Agency for International Development, part of the State Department.

This difference was very

important as it placed the operations of the Joint Commission outside

the arena of diplomacy. As things evolved, there was little communication or cooperation

between the two US departments, Treasury and State. This was because the basic

issue was about money. Most non-military "foreign aid" is US

government funded with funds allocated by congress funneled through the State Department and

the Agency for International Development. In the case of the Joint Commission, the entire

cost of all the programs was borne by the Saudi Arabian government, and all the funds to support

the programs were transferred from the Saudi Ministy of Finance to the US Treasury Department each

year in advance of the annual program implementation. This was an extra-budgetary transfer of

billions of dollars without any congressional or other oversight. The Treasury Department then

administered the money and generally made certain that much of it flowed in ways that routed

into that department and its personnel.

The whole process was largely run through the Joint Commission office in Riyadh, JECOR, with

of course, plenty of supervison from an office in Washington created for that purpose and headed

by a "Deputy Under Secretary of the Treasury".

It was supposed to work something like this. When a Saudi government agency felt it needed

some manner of assistance from a counterpart U.S. government agency, JECOR staff would work

with the Saudi agency needing assistance to develop a "scope of work". JECOR then identified

a US government agency with the staff and expertise to address the stipulated

need(s), prepared a work plan and staffing requirement for the project, identified

necessary local resources and then worked up a budget for review and approval by the Saudi agency,

the Saudi Ministry of Finance, and the U.S. Treasury Department. Once the plan and budget

had been approved, the money was transferred to the US Treasury Department from the Saudi

Ministry of Finance. At Treasury all the JECOR money was kept in an

interest bearing account, with the interest earned being retained in the account.

It should be noted that money for a JECOR project was "extra budget" for the Saudi Agency as well.

Thus, there was incentive on both side to develop and implement projects.

There was a lot of money at play. Multiple billions of dollars. To get a sense of how much money

was involved, consider this "factoid". The Saudis finally pulled the plug on the Joint

Commission sometime around 2000 at the time the Kingdom began to first run significant deficit budgets,

(something JECOR planners had taught them how to do). Even the Saudis felt they could no longer

afford the Commission. The Joint Commission however continued to operate with money

remaining in the Treasury account. The accumulated interest on those prior budgets funded continued

operations for nearly ten years, at annual budgets of billions, as the various projects wound down.

And all that money was simply the interest earned on all the Saudi money that Treasury had kept on hand

through the decades before.

Throughout its existence, JECOR maintained a headquarters of its own, separate from the US Embassy

in Saudi Arabia. It managed an extensive network of support for the many projects (dozens) it operated

including housing for staff, both U.S. citizens and local workers. It operated a fleet of cars provided

to project staff as well as cars and drivers for staff and families, as the U. S. staff there were

in country with families and were provided full support from housing and transportation to schooling

for their children. It was a pretty cushy life and the increased pay and favorable tax regulations

made it a very good assignment for mid-level government employees.

The Saudi Military

There were plenty of U.S. military personnal in Saudi Arabia at the time we were there.

Many were there in a training capacity. There was a major training facility in Riyadh,

known to us as "USMTM" - for U. S. Military Training Mission. It was established in

1953. The trainers there dealt

with the Saudi Army and Air Force personnel.

Saudi Arabia at the time did not have much of an army. There was a small force, staffed largely

by paid personnel mostly from Pakistan, which operated the armored units that were part of

a defensive force. The Kingdom did have a small air force, flying American aircraft and

trained by American trainers, who privately told us that the Saudis made excellent pilots.

In addition, Saudi Arabia operated a fleet of AWACS (Airborne Warning and ControlSystem) aircraft.

These operated out of the military airport in the northern part of Riyadh, and there was one in the

sky at all times. Although the crew on the aircraft were Saudi, there was always a U.S. co-pilot

and electronic warfare specialist on board. It was rumored that intelligence from the Saudi AWACS

planes was shared not only with the U.S. but also with Israel.

The kingdom did however have a "National Guard". This was the personal army of the King made up entirely

of men from bedouin tribes which had pledged personal loyalty to the King, renewed every

year. This Guard was organized by tribe and service in it was voluntary. The Guard was trained by U.S.trainers

at a huge base just outside Riyadh, known as OPM/SANG, established in 1965.

Our project team got to know the health team at the hospital

there during our time of stitching together an emergency medical services system for the

area and coordinating ambulance care locally. The SANG hospital was an excellent top level trauma

center, due largely to the frequent training mishaps there.

It was the National Guard that defended the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1987 during the attempted take over

of the shrine by Iranian backed Shia Muslims during the annual pilgrimage. Privately, we heard that

the Guardsmen had stood their ground against a huge, armed crowd, ultimately preventing the

entry into the mosque and killing large numbers of the crowd, despite heavy casualties of their own.

The American trainers we knew were very proud of their trainees and told us that there were over 1,200

people killed during the episode. That number has never been confirmed by any official source, and

the bodies were reputed to have been buried in mass graves in the desert and the individuals simply reported

as "missing".

One important principle of US - Saudi military cooperation was that there would be no US (or any

other foreign nation's) combat troops stationed within the Kingdom. This was a very important aspect

of the relationship and important to Saudi Arabian leadership to show their Arab neighbors that

the Kingdom was not a pawn of the United States.

This "understanding" was still very much inforce during our time there in the mid 1980s. The Iran-Iraq

war had greatly heightened security concerns in the region and there was a US Naval presence

in the Gulf. And the AWACS operated by the Saudis were an important part of efforts to

monitor and influence the outcome of the war. But, although

US personnel flew aboard the AWACS aircraft, for example, they were in the Kingdom for short term

roations, about 6 weeks, not permanently stationed there. The only long term US military personnel

were trainers.

Things changed with the Iraq invasion of Kuwait in 1990. U.S. President Bush's administration

prevailed upon the King of Saudi Arabia to allow U.S. combat operations within the Kingdom. Although

the agreement to permit this was short term, until the expulsion of Iraqi forces from Kuwait,

on-going concerns about Iraq's intentions prolonged the stay. This presence of U.S. forces

and the behaviors of U.S. troops, who were not always sensitive to the conservative traditions

of the Saudi populace, led to a strengthening of the deeply conservative fundamentalist

Islamic Sunni factions in the Kingdom. These people had always been critical of the royal

family, mostly for their "western" ways and their opulent lifestyle, but the criticism

gained little traction among most of the population, who enjoyed relative economic prosperity

and security through the policies of the government. But the tensions around the presence

of foreign combat forces shifted the dynamic and resulted in increasing support for the

most conservative elements in Saudi society.

That shift in societal attitudes about "Americans" coupled with the return to the Kingdom

of Saudi nationals, who had fought with the "Mujahideen" in Afghanistan against the

Soviets and the Soviet-backed Afghan government during 1980 - 1990 created fertile

soil for a home-grown, Saudi led, Sunni Islamic fundamentalist movement. The Saudi

government had always had a somewhat uneasy relationship with the more conservative

elements of the society, the Wahhabi, but found itself faced with a new fundamentalist

movement prepared to use terrorist tactics to bring about the downfall of the royal

family government and the expulsion of all foreign troops from the country. And this

new movement had plenty of participants who had combat training (mostly by the U.S.)

and experience in Afghanistan. And, as well, they had a network of contacts with

like-minded people outside the Kingdom. The mix proved to be deadly and led to the

1995 car bomb attack on the headquarters of OPM/SANG in Riyadh, killing 7 and wounding 70,

the 1996 truck bombing of the military facility at Khobar Towers killing 19 and wounding

over 400 and later in the 2001

attacks on the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon.

What's in a name?

In the Arab world, it is said you can tell all you need to know about

a man from his name.

In general, a person has a personal name or names and a family or tribal name.

For example, the name Mohammed Ghatani or Mohammed Al-Ghatani, identified

the person as Mohammed from the family (clan, tribe) the Ghatani. Note

that the name Ghatani is also transliterated/spelled as Qahtani.

In Saudi Arabia, most people know which tribes pledged loyalty to

the founding king, Abdul-Azziz, "Ibn Saud", and if you are a member of

one of the earliest families to do so, you are regarded with greater

respect and regarded as more trustworthy.

Also, many names are associated with particualar regions of the country

there. In the example above, the Ghatani (Qahtani) are a people from the south-

western part of Saudi Arabia, in the Tihamah, the coastal plain, or

the Asir, the mountains there. The Ghatani are found both in Saudi

Arabia and adjacent North Yemen.

To further identify an individual, the name may include the

name of the persons father as part of the individual's name.

The first king of Saudi Arabia was named

Abdul Azziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud. Which roughly

translates as "Abdul Azziz, son of Abdul Rahman, of the Saud

family". Women can be identified similarly. The mother of

Abdul Azziz, wife of Abdul Rahman, was named Sara bint

Ahmed Al Sudairi. This translates as "Sara, daughter of

Ahmed of the Sudairi family".

King Abdul Azziz had multiple wives, one of which was

Hussa bint Ahmed Al Sudairi. He had more

sons with Hussa than he did with any of his other wives.

Although the King had a total of 45 sons of which about

36 survived to adulthood along with many daughters,

the seven sons with Hussa are known as "The Sudairi Seven".

Although only two of the seven have become King,

Fahad and Salman, the group has been and remains

extremely important and influential in royal politics.

Complicating things a bit is the common use of nicknames

for Arab men and women. The first King Abdul Azziz, for

example, was frequently known as "Ibn Saud". Ibn is a

variant of "bin", so this roughly translates as "Son of Saud".

Another common alternative name, nickname, uses the word

"Abu", which means "father of". So a man with an eldest son

named Khalid might be known as "Abu Khalid".

First names are often aspirational, based on some hoped-for

characteristic, or the Arabic equivalent of the name of a

character in the Bible or the Quoran. Abdullah, for example,

means "servant of God". Mahmoud means "Worthy of Praise". Hamdi

has a similar meaning, but also means "one who remains close or

steadfast". Saifan means "Sword of Allah". There are feminine

equivalents for all these as well as humdreds of other names

for girls. Aliya (Gift of God), Jamilah (Lovely), Fatima (Captivating,

also, one of Mohammed's daughters) and so forth.

Also, there are biblical names such

as Ibrahim (Abraham), Yusif (Joseph), Daoud (David) for

boys and Sara (Sarah) or Mariam (Mary) for girls.

And, of course, within families, or among friends, individuals

have other names, based on some characteristic or behavior.

Ibrahim is often shortened to "Brahim", for example.

Christian Arabs often use different first names or

variations of spelling of the names. Also, there are

different ways of saying "son of" or "father of" among

Christian Arabs. Use of the connector "Abi", such as in

Daoud Abi-Nader, indicates the person is a Christian, likely

from Lebanon or Syria.

In a conversation with a physician colleague at the

American Embassy in Riyadh, he played the Middle Eastern

"name game" with me. His name was Daoud Kantalflas and

he asked me to tell him the origin of the name, and thus

his birthplace. The first name was Daoud, the Arabic for

David. The family name Kantalflas, was of Greek Origin

and refers to the "candle-lighter" in Orthodox Church

services. An Arabic first name and a family name of

Eastern Orthodox origin? He was from Jerusalem, born

there before the 1947 war in the days when people of

all faiths and all ethnic origins and all nations lived

there and co-existed peacefully.

I once met a man with the last name / family name of

"Al-Andes" and we talked for a while, going back some

generations to trace the names to see if there was some

connection. Our name is a version of a name found in Germany

and spelled variously in the U.S. as Andes, Antes, Andis,

Antis. Although there are hints in the family oral history that

it may have originated in ancient "Gaul". Caesar's Gallic

Commentary mentions a tribe by that name, the Andes. My

Arabic acquaintance however, traced the origin of his

family name back only for a few generations, to a grandfather,

or perhaps a great grandfather, who acquired the name as a

nickname as a child. It meant something like crybaby or

one who fusses a lot as a child. The name stuck, and his

progeny then became the Al-Andes tribe.

Two quick thoughts on the Arabic language releated to

names and the origin of names.

The definitive article in Arabic is usually transiterated

as "Al" in English. So in the story above, the tribe

mentioned would be the Al-Andes. If you refer to the door,

it is Al-Bab. And God is Al-Lah (The God, the One God).

But the definitive article changes when the word following

it starts with an S or an R. So, the city of Riyadh is

actually spoken or written as Ar-Riyadh. And the family

name Sughair would be As-Sughair, not Al-Sughair. So, to

be strictly correct, the royal family name would be As-Saud,

not Al-Saud, although the latter is more commonly used, even

in Saudi Arabia.

Also among Arabic speakers, there is a different time sense than

among westerners. This is perhaps a function of the language, which

indicates future tense and past tense by adding a prefix to

the root stem of the present tense. The past tense is amost

always a past pefect tense, indicating the action has been

completed. Also, verbs are modified to reflect such things

as mood, active or passive voice, and others. Sometimes the

differences are subtle, such as the doubling of a letter or

using a different vowel, and sometimes there is no difference

in how the word is written, only in pronounciation. Because

everyday written Arabic includes only the consonants and

omits the vowels, it renders the language somewhat imprecise

at times. Only in the Koran are all the vowel markings always

present, as the language in the Koran is not to be misunderstood.

So, spoken Arabic often omits or elides some of the verb

prefixes and suffixes and speakers tend to use the present

tense stem of a verb in casual conversation. This practice

often slides over to the English used by a native Arabic

speaker. So we learned that when a Saudi colleague at work

described some event seen on the street on the way to work,

he may be talking about something that had happened to him

that morning, something that had happened to him at some

time in the past, or something that had happened to a

friend or relative today or sometime in the past. This

different sense of time is an important thing to remember

about the Arabic culture. It keeps the past fresh and

part of daily life. And also keeps alive past wrongs or

grievances from generations ago.

Remember that most Arabic Muslims can recite the names of

their direct ancestors all the way back to the time of

the Prophet, Mohammed.

Saudi Traditions - Origins and Changes in Culture

One day at the Red Crescent headquarters, the chief of the

neurosurgery department arrived for an EMS planning meeting. We

were chatting before the meeting and he shared with me that he

had recently taken a bus in Riyadh and had been surprised

to see several people on the bus reading the local paper and was

delighted by this. I did comprehend his happiness over such a

simple and, to me, commonplace thing. He explained that many

aspects of Saudi culture and customs were rooted in the nomadic

life style of earlier generations. Nomads don't have books,

other than a Koran, because they are so heavy to carry about.

They don't have furniture, either, which will lead to the

next paragraph. Although the literacy

rate in Saudi Arabia was pretty high, most people still had

not developed a habit of reading. So my acquaintance

had been very happy and

hopeful to see ordinary Saudis reading the paper on the bus.

Something, he said, that he would not have seen even a year or

two earlier.

Probably for similar reasons, in the more traditional Saudi homes,

there was little furniture. In what would correspong to

the living room, the "maglis" or

sitting room as it was known, where the men hung out when

visitors came, most homes were furnished with carpets on

carpets and large bolsters and pillows along the walls. You

can see two examples of a sitting room above in the section

about Saudi hospitality. In the adjacent room, often separated

from the Maglis by a set of double doors or pocket doors, the

dining room was also sparsley furnished. There was no dining

room table and chairs, as meals were served on great trays placed

on the carpeted floor and people sat on small cushions to eat.

In homes of more "westernized" Saudis or homes of Saudis who

frequently entertained westerners, the furnishings were much

the same as in an American home, with large couches, chairs,

"coffee tables", lamps, etageres, knick-knacks, and sometimes

family pictures. Dining rooms had large tables with chairs,

side boards, and so forth, and meals were served individually

with guests seated at the table, provided with plates, and

all the knives, forks, and spoons you would find at home.

Sometimes, when dining in a traditional home, or when eating

Kebsa on a camping trip, one might be offered a spoon, or

find one discreetly placed just to the right hand of where

the host was to sit, the spot where you, as honored guest,

were to sit. It was a point of pride to either decline the

proffered spoon, or ignore the spoon found at your seat. On

some occasions, the host might select the best, most tender

and tasty portions of the meal and hand them to you. This

was a way of honoring the guest.

In many respects, the ordinary Saudis tend to look back on

their former desert life through a romantic lens. Saudi families

commonly go camping or picnic in the desert around Riyadh, perhaps

to capture some of this remembered past. Even though few

Saudis today were true nomads, Bedouin, the desert and

the severity of life in a desert setting permeated every

aspect of life in the Kingdom for many generations. Even

the Saudis who lived in their cities interacted and

interfaced constantly with the desert and desert dwellers.

Even those who lived and farmed in the fertile

coastal plains in the west or fished the Red Sea or

the Gulf, always lived a precarious existance.

There are other ways in which the early history of

survival in the desert affects the culture. The generous

hospitality of Saudis, the sharing of food, and the genuine

desire that a guest be taken care of to the best of the

host's ability probably stem from the basic need to take

care of other people, even strangers, when in the hostile

environment of the desert. It is said in Saudi Arabia, that

if you are camped in the desert and a stranger approaches you,

it is your duty to provide the stranger with food and water and

rest for three days. At the end of the third day, it is permitted

to ask politely whether the stranger will need any provisions

to continue his journey. This hospitality is to be offered

even if the host recognizes that the stranger is in fact

a mortal enemy or member of an enemy clan.

In warfare, there was another tradition. Should a raiding party

fall upon an encampment of an enemy clan, it was permissible for

the raiders to kill all males over the age of ten or so, but the

women and female children and males under the age of ten were to

be spared. And when the raiders departed, they were to leave

three days of food and water for the survivors they left behind.

One could certainly question whether either of these storied

traditions were ever honored, but both seem to support the

notion that life in such a difficult and hostile environment

would certainly affect how even enemies treated each other and

that there must have been some honor code about that. After all,

westerners still accept the concept of chivalry in the

middle ages and many nations subscribe to the Geneva Conventions

about the conduct of modern warfare.

Security in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is a Muslim nation. Official statistics state that

the population is 100% Muslim, with 85-90% being Sunni and the remaining

10-15% Shia. But this number reflects only the number of Saudi

citizens, and of the reported 34 million population in 2021, a

number likely exaggerated, some 25 to 35% are foreign workers. That

number also is questionable and varies considerably depending on the

source. Saudi sources, for example, report there are about 1 to 1.5

million Pakistanis in the Kingdom; Pakistani sources put the number

at 2.5 million.

The actual population of the nation is regarded by the

government as a security issue.

Saudi Arabia exits in an unstable region and has neighbors that are

fundamentally not friendly to the Kingdom for several reasons. First,

the nation has plenty of oil and has developed and sold its oil

through alliances with western nations. Second, much of the money

from the sale of oil has benefited the royal family, which lives,

for the most part, a life of opulance that is hard to imagine. Third,

the Kingdom had not developed a large military and did not participate

with other Arab nations in military campaigns against Israel. Fourth,

the Saudi government, which is basically the royal family, constantly

reminds Muslims world wide that the two holiest sites in Islam, Mecca

and Medina, are in Saudi Arabia, a very sore topic with

Shia Muslims, who have vowed to take the holy sites from the

Saudis, who are Sunni Muslim. And the Kingdom is thought to profit

greatly from the annual Haaj pilgrimage, which all Muslims,

Sunni and Shia are to perform. And Fifth, Saudis are

generally perceived as arrogant and rude when traveling abroad,

especially in the Middle East but also in areas of Europe where

other Arabic people live or vacation. Saudis are, in fact, known

as the "Americans of the Middle East", which is not a compliment.

So, because of the fundamentally hostile environment that

the Kingdom exists in, the Saudi population numbers have been

inflated for years. During the JECOR years, there was a

data processing and statistical analysis project, STADAP.

That project was also charged with conducting a census and

reporting the results to the government. The initial count sometime

in 1985-86 showed

a population of Saudis around 1 to 2 million and a similar, perhaps

larger number of foreign workers. Discussions with the royal

family and government officials negociated the final figure upward

to a Saudi population of around 6 million and fewer foreign workers

but even today, total population is reported as around 12 million.

The actual Saudi population was a very sensitive security issue then

and I suspect it is today. In 1985, Iraq had a population of 15 million

(today around 45 million) and Iran had a population of 45 million

(85 million today). Iraq has a significant Shia population, about

60% of total population, concentrated in the southern areas, near

the Gulf, and Iran is almost entirely Shia Muslim.

Whatever the actual population of Saudi citizens is, some

10 to 15% of them are Shia Muslims. The Shia population is concentrated

in the Eastern Province, where most of the active oil fields

and refineries are located and where many of the foreign workers

from the U.S. and Europe are located, and where the Saudi Shia

population is subjected to pretty constant propaganda from

Iranian sources just across the Gulf. Thus, the Eastern Province

is and was regarded as the most potentially unstable in the

Kingdom, and the greatest security risks were thought to likely

arise there.

However, due to several factors, the security risks and actual

attempts to bring down the Saudi government in the 21st century

arose internally among Sunni Muslims. This was probably for

several reasons.

First, as mentioned above, there is and was

some resentment of the royal family among ordinary Saudis. This

resentment was ameliorated to large degree, at least during the

time we lived there, by the very generous welfare state created

by the government. But, as oil revenues changed and costs of

defense increased in the 1990s, the generosity of the welfare

state subsided. That, together with the significant growth

of the population, including the royal family, decreased the

share of government largess available for each ordinary family

while the royal families took and increasing share due simply

to there being more royals to take care of. This resentment

of the royal family, which is synonymous with the government,

was exploited by the Shia factions, who criticized the royals

for their life style, even for distributing pictures of the

King, which to them were forbidden "graven images", and for

the way the minority Shia were treated. And the resentment was

also exploited by the growing fundamentalist Sunni factions, who

criticized the royal family for their "western" ways, for

their alliances with the U.S., and for the continuing

presence of U.S. military forces in the Kingdom.

Saudi Arabia had come into existence in part through the

cooperation and collaboration between the original King, Ibn

Saud, and his family, and the members of a fundamentalist Sunni

Muslim sect, the Wahhabi. This cozy relationship was well-managed

by Ibn Saud's successors through the 1980s, but began to cool

in the 1990s. The U.S. (CIA directed) support for guerilla

forces in Afghanistan

resisting the invading forces of the Soviet Union was a

complicating factor and greatly affected Saudi security in

later years. These guerilla forces included large numbers

of Arab Muslim fighters, known as "Mujhideen", who recieved

military training and weapons from CIA trainers at bases

in Pakistan. Many Mujhideen were from Saudi Arabia and

returned home having had training and experience in

battle and also having had, either before or during their

time in Afghanistan, exposure to fundamentalist

Sunni Muslim doctrine. These returing fighters made

up a core of anti-government activists who soon

engaged in a domestic terror campaign in the Kingdom.

The U.S. support for and training of Saudi Mujhideen had

was a profound additional destabilizing factor for the

internal security of Saudi Arabia.

A significant second factor in increasing unrest among

the Saudi population was the combination of several things, both

unintended consequences of otherwise beneficial social programs.

The Saudi government had encouraged population growth among

Saudi citizens for years through generous social support systems

including housing, food and water assistance,

free healthcare, and other benefits that enabled large

families. The Kingdom had always had a high birth rate.

The Saudi birth rate was 47 live births per thousand

population in 1960 (U.S. was 22), 43 in 1980 (U.S. 15)

and that, together with medical services that reduced the

infant and child death rate and prolonged life, further

increased the size of the Saudi population. The Saudi

birth rate in 2000 was 17 (U.S. 12), probably reflecting

social and economic factors mentioned above that made larger

families less affordable.

During the mid and late

20th century, the Saudi government also implemented an

educational system that provided free

education through graduate school for all Saudis.

This free education included support for

study abroad, including tuition and living expenses, for

the student and his/her family. Many Saudis we met in

the 1980s had been educated at U.S. or European universities.

These students returned with an excellent education

and with fond memories of student days abroad, an

understanding of western culture, and friends in

western nations. In the late 1980s, the Saudi

government almost entirely ended its support for

advanced study abroad both as a cost saving measure

and because the internal Saudi university systems had

developed to a point where they were regarded as

equivalent to any in other nations. Thus, by the

1990s, Saudis with advanced degrees were likely to

have studied in Kingdom and not have experienced

student life abroad.

The educational system produced increasing numbers

of highly educated Saudis. But there were not enough jobs for

them in Saudi Arabia There were, for example, excellent petroleum

engineering programs at multiple universities in

Saudi Arabia, turning out thousands of graduates

per year. But how many petroleum engineers can a

nation employ?

In short, through generous, well intentioned, social

programs to enlarge and benefit the general population, Saudi Arabia

produced an increasing number of highly educated people

(men and women) with high expectations for a well-paying

career at home, who could not find a job. An excellent

population for exploitation by those creating or

fostering discontent and division.

Naturally, the Saudi government took security seriously. And,

according to American security personnel with whom I spoke,

they were really, really good at it.

For example, in our project, some of the personnel

came to me with

concerns about a fellow from Palestine who worked for

JECOR and was talking about how difficult life was for

Palestinians living in the West Bank due to Israeli

government policies and actions. This fellow even shared

some literature with them that had originated with the

Palestine Liberation Organization, considered a

terrorist organization by the U.S. government. At their

request, I reviewed the situation with the security

people at the American Embassy. They were not concerned

about

the report, saying that they (Americans) did not

worry at all about Palestinians. This was for two reasons.

First, most Palestinians were intensely pro-American and

were simply hoping that some day the U.S. would

realize the situation in Palestine and force Israel to

do the right thing. And second, the Saudi security

people already closely monitored all Palestinians in the

Kingdom. The Saudis even collected a sort of tax from

the salaries of Palestiniand and forwarded it to the PLO,

so the relationship was a good one.

It was the Pakistanis that the Saudis and the

American security personnel worried about. And, in

fact, the several small bombings that happend in Riyadh

during our time there were all perpetrated by Pakistanis.

A couple of them were thought to have been directed at

Americans, as they happened at places frequented by

Americans, such as a pizza restaurant.

In addition, there were three kinds of police in Saudi Arabia, not

including military and customs and immigration police.

There were the Security Police, the General Police (including

Traffic Police), and the Society for the Prevention of

Vice and the Promotion of Virtue ("Mutawah"), the Religious

Police. The latter had little enforcement authority, but

could make life pretty miserable for Saudis and for

other Muslims. They had little they could do to

harass westerers, other than verbally. The Traffic Police

are discussed further below in the section on

Law and Lawyers in Saudi Arabia.

The Security Police today are part of

the Saudi Mabahith or General Investigation Directorate, which

was created in 2017 by merging the domestic security agency

and the counter-terrorism agency, perhaps a recognition of

the growing threat of home-grown terrorism. This Directorate

has Ministry level authority.

The Saudi Security Police are a secret police.

The officers of the Mabahith have the authority to investigate,

surveil, arrest, and detain individuals who are deemed to be "threats to

national security". The definition of a threat to national security

has enlarged over the years to include not only terrorists

but also members of the political opposition. The Mabahith

is thought to operate several prisons in the country, which

are separate from the general criminal prison system. The

power of the Security Police has increased over the years

since we lived there, paralleling the increase in threat of

terrorism within and without the country.

Fortunately, we had no contact with the Security Police while

we were there.

Law (Shari'ah) and Lawyers in Saudi Arabia

Criminal Law Inforcement

The General Police in Saudi Arabia are part of

the Directorate of Police or Public Security, part

of the Ministry of the Interior. These are civilian officers

responsible for law enforcement in the Kingdom.

The General Police force has several operating Departments:

The Police Department deals with ordinary criminial matters

and operates much as similar organizations in other countries.

They refer arrested individuals to the court system for prosecution.

The Saudi legal system, including the courts,is based on Shari'ah,

the body Islamic laws

derived from the Qur'an and the Sunnah (the traditions) of the

Islamic Prophet Muhammad. Shari'ah also includes Islamic

scholarly opinion (Ijma) developed after Muhammad's death, but lacks

the tradition of judicial precedent that is a cornerstone of

American "common law". Most trials or court appearances in

Saudi Arabia are "bench hearings", that is, the accused appears

before a judge, who makes the decision in the case. This lack

of the tradition of a jury trial, a trial by ones peers, is

a second big difference between Sharia and the American system

of law.

These differences mean that a decision in any individual case

is made by a "judge" who bases the decision on his understanding

of Shari'ah law together with any mitigating circumstances. There

are few standardized procedures and an accused is not always

represented by a lawyer. Most cases,

both civil and criminal, are seen in a Shari'ah Court. The Saudi court

system consists of three main parts. The largest is

the Shari’ah Courts, which hear most cases in the Saudi legal system.

Reforms to the judicial system in the 1990s and 2000s created

administrative courts, and courts dealing with labor issues, and

other specialized areas, and

a Supreme Judicial Council. But the King remains the final, highest,

"court of appeal" and source of pardons.

Also, within agencies and Ministries, there were and are separate

councils and individuals to ajudicated certain disputes or matters

within the jurisdiction of the agency. More on that in the

discussion of the Traffic Police.

So the Police Department officers dealt with violations of

criminal law. The crimes varied from relatively minor

crimes such as fighting though more serious things such as

petty theft to serious crimes such as murder. Criminal law punishments

could be very serious and include(d) public beheading,

stoning, amputation and lashing. Serious criminal offences included

not only crimes such as murder, rape, theft and

robbery, but also apostasy, adultery, witchcraft and sorcery.

While we were there, public beheadings were less common that

recent years, when excution of "terrorists" and dissidents has

increased. Many executions were for non-violent crimes, drug

use or drug smuggling being a common capital offense. During

our time, two men were arrested for stealing gold from the safe

of a gold merchant in the market in Riyadh. Although it was said

publically that a death sentence only was given for serious crimes

such as murder or rape, it was also given to individuals who

were "habitual criminals". In the case of the gold thiefs in

Riyadh, they were accused of "crime against the national economy"

and one was determined to be a habitual criminal, as he had

several parking tickets on his record. The latter one was beheaded.

One of our Saudi EMS trainers had worked for a time as an ambulance

attendant and nurse and had attended several public executions and

ambutations. According to him, the persons being beheaded were

heavily drugged and sedated before the execution, to the point where

they needed assistance even walking to the execution site. Once they

had knelt before the swordsman, the death came quickly. Those having

a hand amuputated for habitual thievery were also sedated, and a

physician marked a line on the wrist where the swordsman was to

make the cut. After the amputation, the amputee was further medicated,

taken to hospital by ambulance, and the amputation surgically

completed in the operating room by surgeons.

I also talked with other western health care workers stationed in

rural areas and learned they had witnessed (fatal) public stoning of a woman

accused of adultery.

Cautionary tales about biblical punishments as they exist in a

present day theocracy, where there is no separation of church and state.

Civil Law, Lawyers, and Contracts in Saudi Arabia

One consequence of the way the legal system functioned, was

that, at least in the 1980s, there were few lawyers in Saudi

Arabia. Whether this was a good thing or a bad thing might be